I like Dragonsweeper. It’s also free. You should go play it in your browser here.

This is perhaps not the most elegant piece of writing I have opened a blog post with, but it’s also all true. Dragonsweeper is a small, clever twist on Minesweeper. It doesn’t cost any money. It won’t eat your entire day. There are no microtransactions, or other bullshit. It’s just good.

To quote the office: “Why use lot word when few word do trick.”

That said, you’re still reading, which means you haven’t been persuaded yet. That’s okay. Maybe you missed the first link. Here, I’ll link to again.

It’s possible that didn’t work either. Unlikely, given the incredible rhetorical barrage I’ve assembled so far, but possible.

It’s important to note though, that since Dragonsweeper is a puzzle game, in order to talk about it, I will be spoiling some of the puzzles. As few as I can! But some. This is your last chance to just back out and play it?

No? Well let’s continue.

Dragonsweeper is a puzzle version of Minesweeper. It uses the general framework of Minesweeper the same way Balatro uses poker: as a structure with so many things grafted onto it that it’s almost unrecognizable. But understanding the general concept or the original will make the initial exposure more tolerable.

Like Minesweeper, Dragonsweeper consists of a grid of tiles. Clicking a tile reveals what’s beneath it. If the tile is empty, just like in Minesweeper, that tile then displays a number of the sum of the surrounding tiles.

Unlike Minesweeper, most tiles on the board are not empty, nor do they contain mines. Instead, they contain monsters. This is a problem for our boy Jorge.

When you click on a monster, Jorge loses health equal to its power. If Jorge goes below zero health, it’s game over. Fortunately, defeating monsters also gives experience, and after collecting enough EXP, Jorge levels up, refilling their health bar.

But after the first few levels, the amount of EXP needed to level up is higher than the Jorge’s total health, and just defeating monsters isn’t enough. Instead, it’s necessary to crack open treasure chests, use healing scrolls, or find some other sources of EXP.

If you’re just starting the game, you will almost certainly die.

And then the real game begins.

This is your Last Chance to Back Out Before I Start Spoiling The Puzzles I Mean It This Time

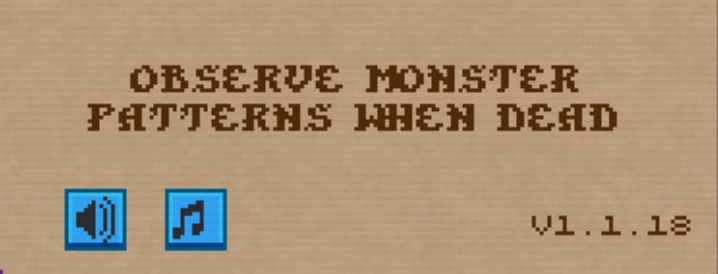

In the corner of the screen is a little tiny purple book. When you click on the book, it tells you which monsters have which values, and how many remain. It also includes this little bit of text.

This right here is the heart of Dragonsweeper. See, Dragonsweeper isn’t truly random. It’s randomized, but after a few death screens, you might notice that the 10 value monster, the Mine King, is always in one of the corners.

Or you might instead pick up on the fact that the Slime Wizard is always guarded by six 8-value purple slimes, and always on the edge of the map.

You might spot that the 4 value gargoyles will always be facing another Gargoyle in a cardinal direction.

There are at least another five or so little patterns and rules like this. There are some I haven’t even found, and there are several that I didn’t spot until I had beaten the game, and was showing it to a friend.

For me, spotting these, and figuring out how to use them is what makes Dragonsweeper so brilliant. It’s very clever puzzle design where learning about how the board can be laid out, and how some things interact is the progression.

Again. Dragonsweeper is really good, and you should play it, and it’s free.

And a request for the developer: please make a full game. I have given you money and I will give you more.