I moved recently, and work has been incredibly busy. So instead of a full review, I want to talk a bit about something that’s been on my mind recently: myself!

I’ll be honest, this was a post about why I have difficultly recommending live service games, but after getting 8 paragraphs in, I realized it had turned into something else. First though, a story.

I was at a board game playtesting event recently where I had just played a large game in an early prototype stage. We were discussing the game’s strategies and elements. Mentioning that I felt the strategies were fair because we all ended with around the same number of points, another person at the table stated that was a bad way of looking at things.

Then that person stated that perhaps I couldn’t understand this because I wasn’t a game designer. I’ll be honest, that made me more than a bit angry. But this wasn’t my space, and also even if I think they could have been a bit less antagonistic with that statement, they were correct.

But it does raise an interesting question. What exactly is my relationship to games?

If I had to choose, I think I’d use the word “Hyper-Enthusiast.” I’m not designer. A few mods, small projects, and an internship do not a designer make. I’m not really a journalist. Yes, I run this blog, but I have no training in it, and I do very few interviews or investigative content. And the term “Aspiring Influencer” makes it sound like I sell protein shakes for $50 a bottle on TikTok.

I would certainly like to have a large audience! But my experiments with modifying the sorts of things I make and how I write are mostly constrained to my YouTube channel. I’m not interested in changing this blog to appeal to more people.

So, going back to how I’d label myself. “Hyper-Enthusiast.” Why don’t I just say gamer?

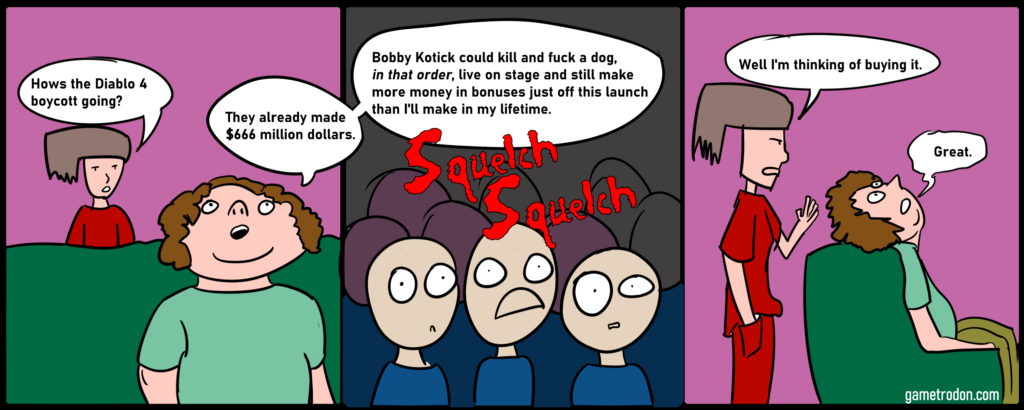

Partly because of shit like this. Partly because Gamer Gate changed the word gamer at least a bit to mean “someone who hates women and minorities” instead of “person who likes games.” It also changed “ethics in games journalism” into “someone who hates women and minorities.” Which is unfortunate, because it is something I care about in the non-dogwhistle sense, but I’m about 8 years late on all of that, so whatever.

But mostly because I view myself as a hyper-enthusiast because I will do a lot of things, and put up with a lot of shit that I don’t think most people will. Even game designers.

I will play unstable alphas, questionable betas, games with subjectively terrible art. I will play games with monetization so expensive they make lottery tickets look like a stable financial instrument.

I will put up with a lot of garbage in search of novelty.

I don’t actually know anyone else like this.

Okay, so you’ve talked about yourself for too much time. Why does this matter?

So this post was going to be a writeup on the difficulty of recommending live service games. There are bunch of parts to my dislike of those games. For one, a live service game changes over time, and by the time you, dear reader, get around to it, it might be completely different than what I played. Or it might just have died!

But there’s a second somewhat more insidious reason, and it’s the real reason that this writeup was just me talking about myself.

A lot of people I know have maybe one or two games that they play at any point in time. They might have a permanent lifestyle game, something like Rocket League, Dead by Daylight, Team Fight Tactics, Apex Legends, PoE, Magic: The Gathering or Dota 2.

Then they might have a second game that they are actively playing through, usually something single player, or maybe a single indie game.

I consume games differently. I also consume games at a somewhat higher pace. And when it comes to live service games, or games with an “infinite” endgame, I generally move on from them fairly quickly when I get bored, or find something more interesting.

And I think this makes be a bad source of information on some lifestyle and live service games. Because I don’t play them in a way that much of their player base is going to interact with them. I will not play them for 100, or 1000 hours. I will play 40 hours, and then I will move onto next week’s game.

Instead of playing one lifestyle game and one other game at a time, I consume games 3-4 at a time. It looks like this.

Type 1 – Space Fillers/Social Games – These are the games I always come back to when I don’t have anything else, or I don’t have effort to engage with more interesting things, or they’re games I play almost exclusively in their base form with other people. Mostly just Magic and Dota 2.

Type 2 – Active Games – These are whatever games I’ve currently picked up and roped people into playing with me. They’ll get played above type 1 games. Right now, they include InkBound, Battle Bit, and Deceive Inc. And it sort of was Friends vs Friends for a bit. More on that in a writeup shortly.

Type 3 – Good One Time Experiences – Any game that I’m enjoying/excited about goes here. If I don’t have anyone to play with, I’m likely to play these. But eventually I finish them, and I don’t usually go back. I actually don’t have anything in this category at the moment, because….

Type 4 – Forced Engagement – These are all the games I’m playing out of some form of either obligation or investigation. Critically, these are not necessarily games I’m actually having fun playing. Some of these I have played out of semi-contractual obligation. coughCatchTheFoxcough. Right now this category includes GrimGrimoire (I want to love it, but RTS + controllers is not a great match) and Rain World. (I promised a friend I finished it, but holy shit, Alien Isolation was less terrifying.)

So, now that we have all this garbage, lets go make an actual point.

Okay, so back to the live service thing. Again.

Ultimately, I prize novelty and interesting interactions very highly. I am willing overlook frustrations or flaws that might annoy other people. And because I go through such a high number of games, perhaps never achieving some deep mastery or skill, I don’t really get worn down by small tedious things, or issues that only become apparent at high level play.

And for single player games, that’s fine! But it gives a very specific perspective for games that are in some ways intended to played on and off forever. And it also means that I annoy my friends when I nag them to buy a game for $20, play it every day for a week with them, and then never touch it again.

Anyway, this whole thing ended up being a bit disconnected and rambly, but hey, I’m a bit tired, and I wanted to write something this week. So hopefully you got some value out of it, and if you didn’t, more to come on a Friends vs Friends writeup shortly.