Ed Note: Most of this writeup was written earlier in the year, around Christmas, as was my time in the game. Some of this info may be out of date. Still, Stalcraft is weird enough for me to want to talk about, even if I don’t plan on playing anymore in the near future.

Stalcraft is strange. If you want to know why and don’t care about context, you can skip ahead to the section titled “The Weird Bit.” If not, let’s lay some groundwork, and do a normal review before everything goes off the rails.

Stalcraft is a F2P pseudo-extraction shooter that takes place in the Chernobyl exclusion zone. It’s inspired by the short story “A Roadside Picnic,” using much of the book’s language and terminology. The game’s title is a portmanteau, that thing where you combine two different words into one word. The words in question here are “Stalker” and “Craft”.

If you’re going “Wait, isn’t there another game that does this?” don’t worry. We’ll come back to that.

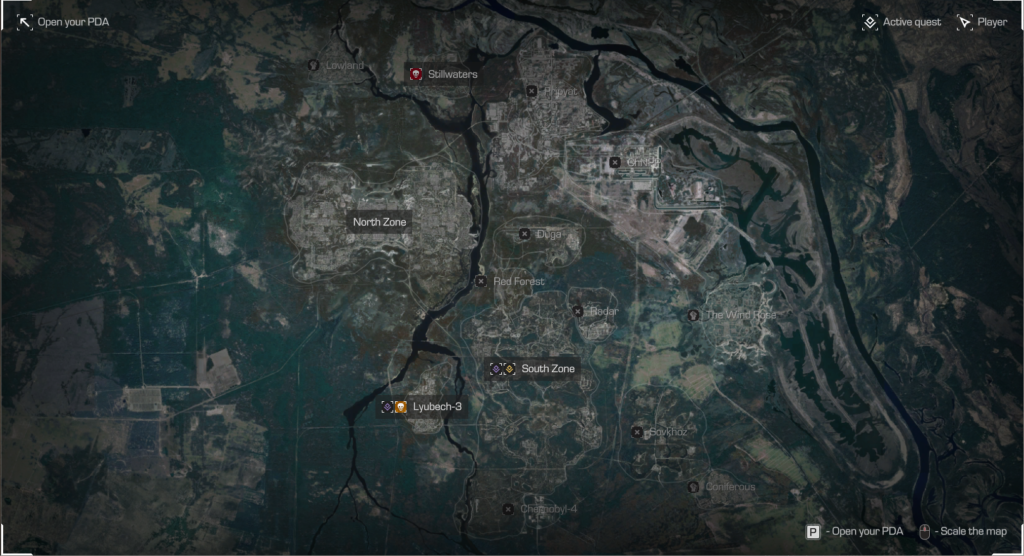

In the game, you’ve suffered a hallucination, and woken up in the Zone—the game’s shorthand for the Chernobyl exclusion zone. You pick one of two starter factions, then you slowly work your way up through the ranks of various bases, completing quests, and traveling across the map deeper and deeper to try to understand what caused you to end up in the Zone.

Gameplay Loop

After creating a character with one of the game’s two starting factions and being given a brief tutorial, you’re dropped into the Zone with a location for the main story quest, a base to return to, and about 5 bullets.

Most of Stalcraft’s gameplay loop takes place across the game’s various zones. Zones are permanently PVP-enabled between factions, and full of enemies

There are two primary parts to Stalcraft’s gameplay loop. Both parts have the player adventuring out into the zone. One is quests, and the other is just general looting and gathering.

A Hunting We Shall Go

Looting and gathering in Stalcraft is fairly simple. Load up your inventory full of bullets, go into the world, travel to various areas, and shoot everything that moves. Since this is an extraction shooter, if you die, you will drop your stuff. Well, not all of it. Some items, like your weapons and armor stay, as do a few quest items. But ammo, snacks, and med-packs are goners.

Stalcraft equipment follows a pretty standard F2P game sort of model, with each piece of being upgraded from older equipment. Doing so requires gathering various zone based resources. For PVP protection, when you’re killed the resources drop, but other players can’t use them.

Instead, they drop in a backpack, a container that can only be opened by the person who gathered the resources in the first place. The result is that it’s not really possible to progress your gear by PKing, but it is possible to PK for a profit by killing other players. Then ransoming their items back to them.

It’s a very slick piece of design. It forces players to engage with the primary system/loop, while still rewarding player killing, and preventing it from becoming a primary method of progression.

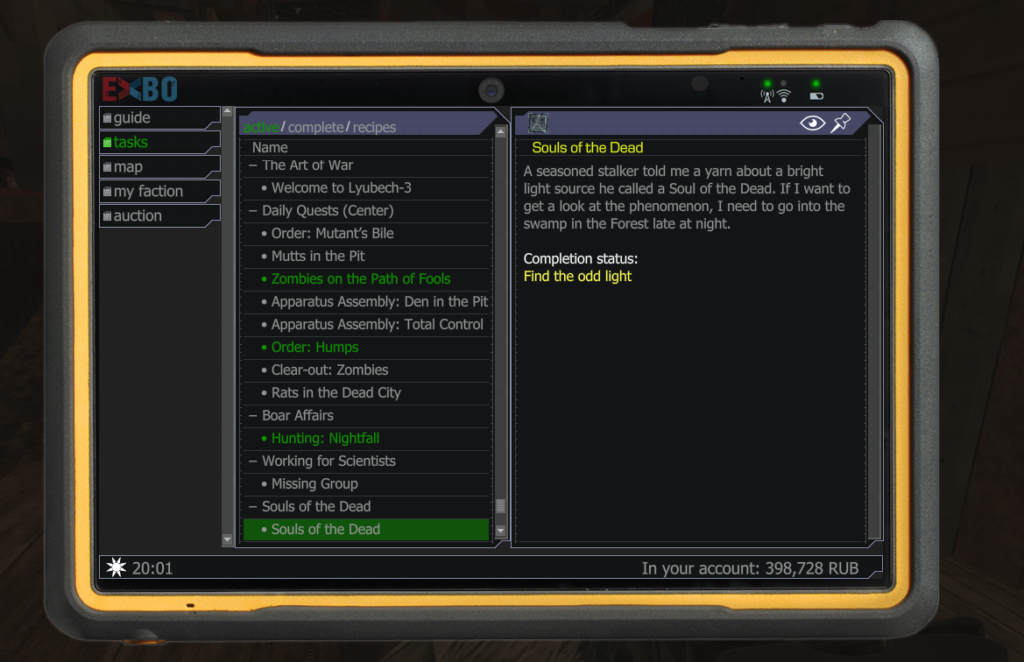

A Noble Quest

Quests, on the other hand, involve the same general “running around trying not to die,” but with a more story directed focus. And for every quest that asks you to kill 10 boars, you’ll get one that’s a bit stranger.

Crawl into a dog kennel, and solve a jumping puzzle.

Solve a mildly frustrating riddle.

Deliver these items.

Into an active volcanic area.

They’re some of the strangest and often incredibly hard things I’ve ever had to do in a video game. Sometimes that’s because they’re janky, and sometimes that’s because… well, you have to cross an entire map of enemy players to get to the place to actually do the damn thing.

The Weird Bit

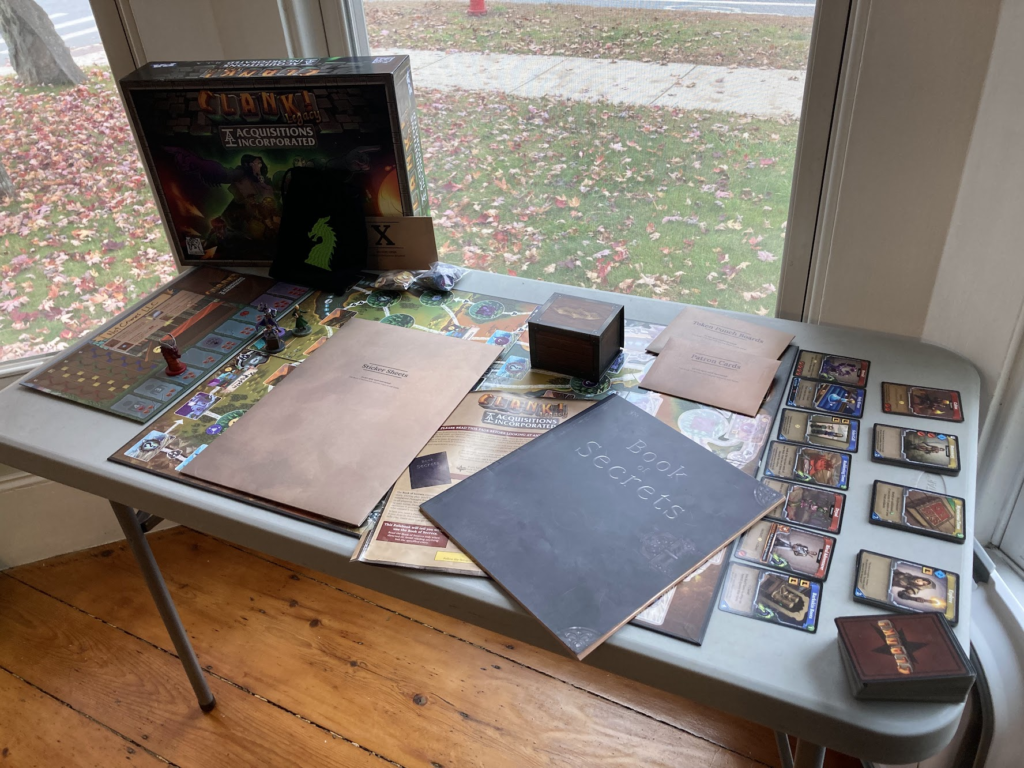

If you’ve been paying attention, or looking at the screenshots, you might have started to put something together. Or maybe you also play a lot of games.

See, while Stalcraft now is a fully standalone game, that’s not what it started as.

You ready?

Stalcraft is/was a mod/private server for Minecraft, with the majority of the game, setting and world taken from the open world game STALKER, and its sequels.

The end result is that Stalcraft is a sort of weird chimera of design. Why are there so many (awful) jumping puzzles and riddles? Because those are comparatively easy to design and implement in Minecraft. Why do all the characters look the way they do? Same thing. Why are the characters and story so weirdly detailed and thought out? Because the whole thing was almost just ported over from another entire game.

To be clear: at no point did StalCraft team, as far as I’m aware, give a penny to anyone above. They just kind of… built someone else’s game inside their own game, and turned it into a generally fun, if aggravating extraction shooter.

It’s incredibly novel, and I’ve just never seen anyone do something quite like this.

That’s all very nice, but should you actually play it?

I played about 70 hours of Stalcraft before I burned out. Ultimately, this is a F2P game, with F2p monetization. Unless you have a huge amount of time or money to burn, you’re not getting to endgame.

That said, it’s an incredibly unique experience in the F2P genre. It can be tense, funny, and aggravating. I got killed and had my corpse camped, only to run back and die over and over again.

There was also a time I killed someone in an enemy faction sort of out of panic, looked at them, realized I didn’t really care if I killed them, rezed them, and then we just looked at each other and ran off.

I think what makes Stalcraft worth playing is how different, weird and janky it is. It’s not the same as something being good, but compared to so many other games, it’s interesting.

In many ways, the general experience reminds me a lot of Sea of Thieves, though slightly more dangerous. You’re dropped into a playground, full of glass, bits of irradiated metal, and told to go play with the other kids, some of whom will beat you up. And sure, the whole thing is cobbled together: those monkey bars are rusting, and some car somewhere is blasting Russian Christmas carols.

But god, if it isn’t fascinating.