I accidentally locked myself in my bedroom this morning, a problem I dealt with by climbing out of a window. This is an actual thing that happened, because I am an idiot.

It does however, provide a useful segue. After managing to get back into the parts of my apartment that aren’t where I sleep, I sat down to play more Tactical Breach Wizards, a game where problems can also be solved via windows.

Most of the time that solution is to shove someone through them.

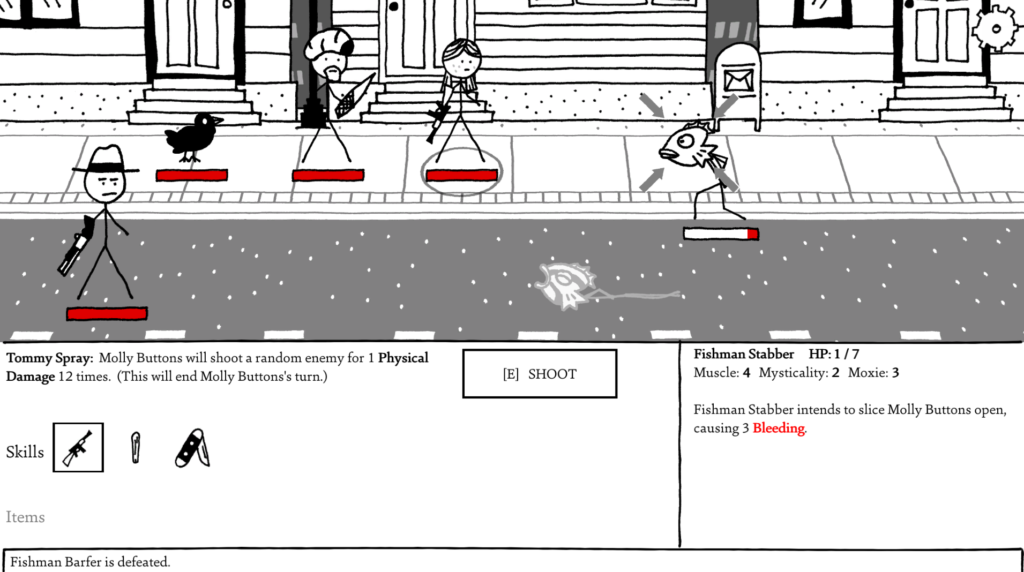

Tactical Breach Wizards is a tactics/puzzle game by Suspicious Developments. If you’ve ever played a tactics game before, you’ve seen at least the bones of what’s on offer here: Given a small set of elite units, you’re forced to fight your way through a series of mooks in a linear campaign, played in turns on a grid map.

Except in Tactical Breach Wizards, where the enemy has assault rifles, chain guns, grenades, and automated turrets, you have a skull named Gary, a wand with a scope on it, chain lightning, the ability to raise the dead, rewind time, and illegal narcotics.

The end result is that there’s a lot less laying down strategic overwatch, and a lot more trying to figure out how to shove someone into a bullet you will fire in the future to get enough mana to make a body double of yourself to hack a turret.

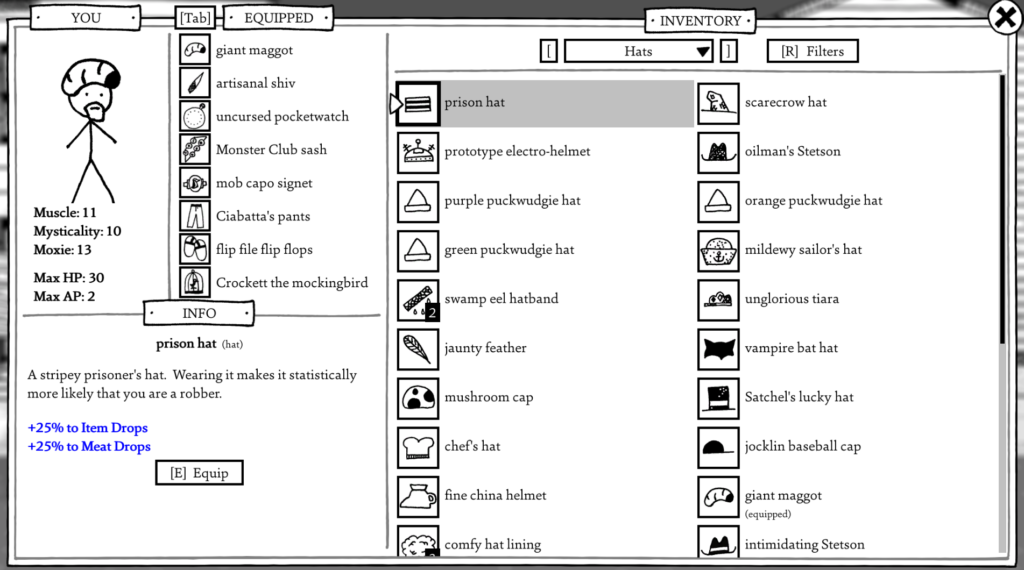

And while the game starts out simple, it builds up to be far more complex. Fortunately, the you also get a much wider variety of tools to use as additional characters join the party, and as you use the perk system to boost those characters.

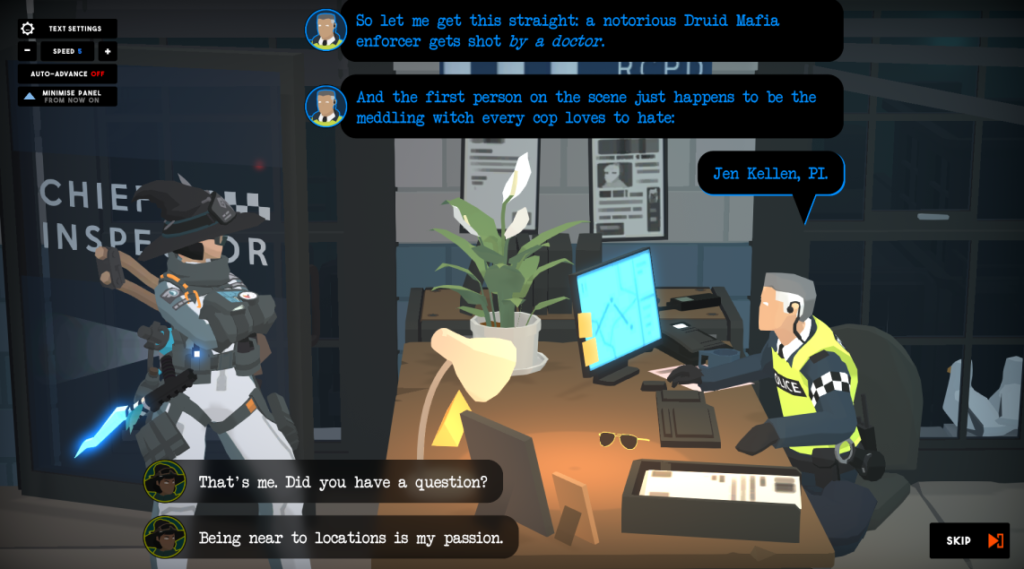

The characters are quite well rounded, and tend to have both a personal consistent theme, and a synergistic gimmick. As an example, let’s look at Jen.

Jen’s basic ability is a “non-damaging” lightning blast. The non-damaging is in quotes because while the shot does not do damage, being shoved into a wall, exposed electrical cables, or another enemy still hurts! Her primary spell is a bit like a boosted version of the shot: a set of chain lightning that can link multiple enemies together and shove them around. Finally, she has a broom that can be used to jump out any window and then enter via another, and a grenade that knocks everyone back.

In addition to all of this, many of her upgrades focus around giving her additional movement phases. The the end result is a character that can move themselves and others. And while on the surface, Jen doesn’t have any direct damage, the ability to throw yourself out a window, jump to the other side of the map, and throw a grenade that tosses 3 battle priests out of a fancy stained glass window is incredibly effective.

At the same time, her kit is also very synergistic with other characters’ abilities. One party member has an ability that allows him to shoot into the future by picking a space with no enemies in it, and shooting if one enters. Another throws speedballs at enemies that increase their knockback taken. Jen can push enemies into the space locked down by the first, and blast enemies debuffed by the second much further.

And pretty much everyone who ends up in the party is designed this way: highly synergistic while also fulfilling a valuable roll on their own.

I don’t really have any complaints about Tactical Breach Wizards, but I do have some observations. I found the game quite difficult, probably because I played on hard. But there were still several levels that felt a bit too puzzle-y for my liking. I enjoyed Tactical Breach Wizards the most when it felt like there were multiple solutions and paths to complete a level, and much less I was trying find the single right solution.

Now, the game absolutely gives you the tools to find those solutions. 99% of enemy actions are deterministic, there’s no penalty to restarting a level. Every single action on a turn can be rewound and replayed. At the end of each turn you can foresee the future, and see how enemies will act. It’s just that I enjoyed the game more when I felt like I was trying to punch my way out of a gunfight, instead of repeatedly restarting because I moved one square to the left incorrectly five minutes ago.

There’s one sort of last big thing about the game I want to call out, but not really discuss: the writing and story. It’s very good. I’ve heard some people compare it to Terry Pratchett.

Pratchett is actually my favorite author, and I’m hesitant to say that that the game as a whole reminds me of Pratchett, or at least Discworld. There are are humorous moments that feel like Pratchett, but the game has a tone much closer to his work that he did with other authors, like All The Long Earth, or Good Omens.

The longer scope means games can do a lot more things than books or movies, and Tactical Breach Wizards jumps around tonally. It’s a buddy cop flick, then it’s an action thriller, and then it’s a war story. There’s a certain level of harshness and melancholy to the later parts of game that feels appropriate. But it’s not a level of harshness I would associate with Pratchett.

The best compliment I can give the writing is this: My investment in the story served to pull me back to the game each time I quit to take a break after finding myself struggling with a level.

More Like Tactical Beach Wizar- wait, they make that joke in the credits.

Overall, I enjoyed Tactical Breach Wizards. It took me around 14 hours and that was on hard while ignoring many of the bonus objectives and extra modes, so if I’d loved it 100% there would still be more to play. It was $20 well spent.

That said, I’m not super interested in playing more because I’m about to start playing through everything else Suspicious Developments have made, including Heat Signature, Gunpoint, and Morphblade. So let’s find out if they’re just as good as Tactical Breach Wizards absolutely is.