There are two types of games that will make me break out a spreadsheet. The first is the sort where there’s so much information, and I’m so invested in the game that I need external storage space. My brain has a lot of things in it, and only so much of it can be ciphers and codes.

The second is a game where I have become so frustrated by continual failure and by design choices that I either do not understand, do not agree with, or some combination of both that I intend to dissect the game to the best of my ability.

He Is Coming is one of the second.

Long time readers may have picked up that my write-ups are a bit formulaic. In part one, I introduce my feelings about a game (done that!). In part 2, I give a general overview of a game, mention its genre, and set up for the rest of the write-up. That’s where we are now, but I actually disagree with He Is Coming on what type of game it is.

He Is Coming calls itself a roguelite RPG auto battler. I take issue with two of those three labels, but as for why, let’s talk about how the game works.

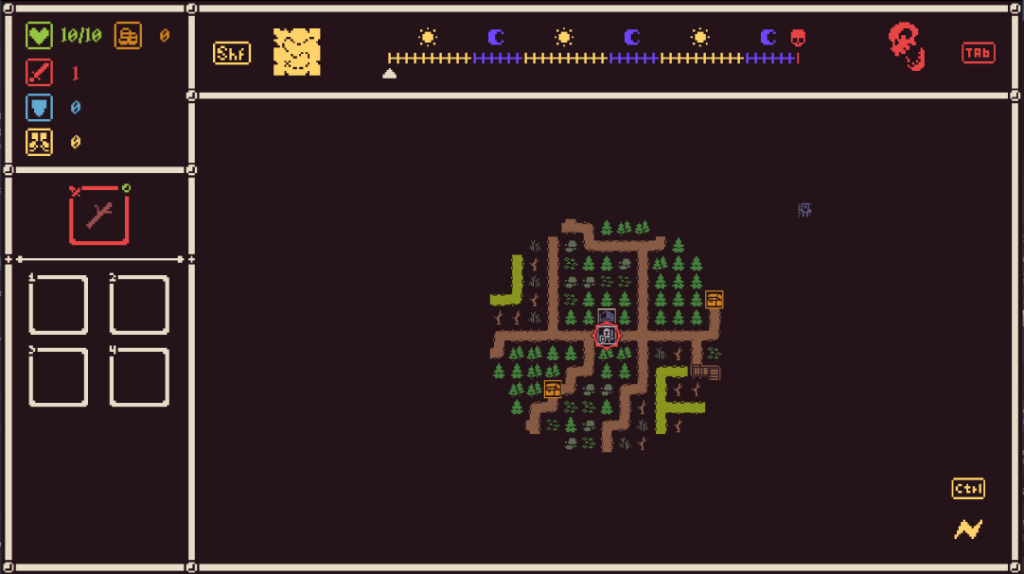

At the start of a new run, the player spawns into a gridded map that they can explore. The map has a fog of war effect, so exploring reveals more of the map.

There are a few special types of things on the map, but the main two are opening chests, and fighting monsters.

(Side note: I’m glossing over the map, and the day/night cycle, and few other things, because they’re not very relevant to my main pain point with the game. I will say that the map is almost entirely an input only sort of thing. E.g. items you pick up almost never affect it.)

Monster battles are auto-battles. There isn’t too much to say here, as the combat is straight forward, and takes place automatically with zero player input. There are four combat stats: health, attack, armor, and speed. Both players and monsters have these stats. Attack is how much damage you deal per strike, health is much damage you can take, armor is a temporary health bar that refills after battles, and speed is who gets to go first.

When you defeat a monster, you get one gold.

There is a bit more complexity to this and how it interacts with items, but I’m not going to touch on it for now, because it’s not as relevant as items.

Chests are the standard 3-pick-1 roguelite item acquisition thing. They tend to spawn next to a single monster, but you don’t need to defeat that monster to open a chest.

The Problem

While I haven’t covered all the game’s features or mechanics yet, I’ve laid out enough to generally describe the “problem” I have with He Is Coming, and it has to do with the bosses at the end of the run.

A run in He Is Coming lasts 3 days. At the end of each day, you fight a mini-boss. At the end of day 3, you fight the zone boss. These zone bosses are always the same boss, and have much, much higher health pools and more difficult gimmicks than the mid-bosses.

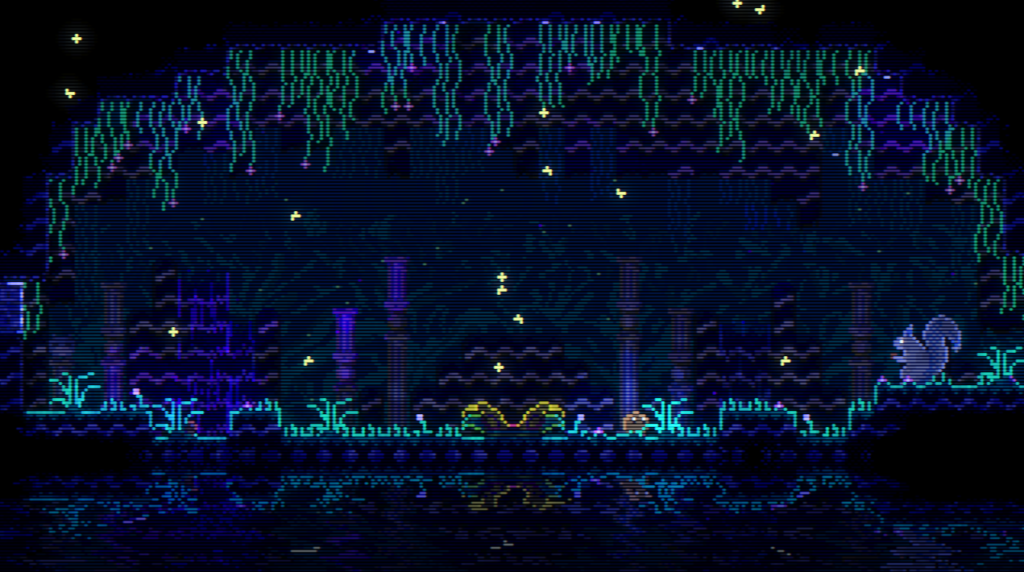

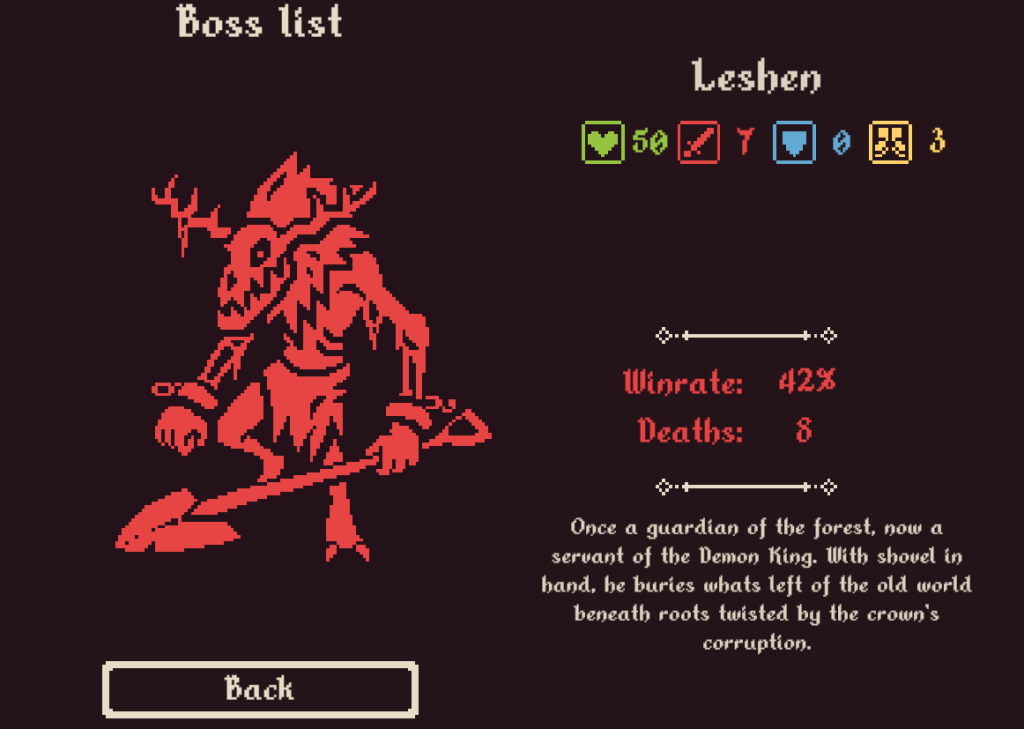

Let’s start with Leshen and the Woodland Abomination as an example.

These are the two forms of the final boss of zone 1. He has far more health than any of the mini-bosses, and he hits much, much, harder then any of them. The end result is that the only way to beat him is to aggressively go over the top, and somehow have a higher armor+life total and higher attack than he does.

Here’s a (incomplete) list of weapons available in the Forest Zone. For the purposes of this discussion, just look at the Effective Attack column.

| Forest Weapons | Base Attack | Effective Attack | Notes |

| Boom Stick | 2 | 4 | |

| Brittlebark | 4 | 3 | |

| Elderwood | 1 | 2 | |

| Featherweight | 2 | 3 | |

| Heart Drinker | 1 | 2 | |

| Hidden Dagger | 2 | 3 | Weird One |

| Ironstone Greatsword | 4 | 5 | |

| Razorthorn | 1 | 4 | Weird One |

| Redwood Rod | 2 | 3 | |

| Spearshield | 1 | 2 | |

| Sword of Hero | 3 | 6 | Set Item |

| Woodcutter | 1 | 2 | No really, you cannot build around this. |

| Battle Axe | 2 | 3 | Lesh has no armor |

| Bejeweled | 1 | 12 | Bad idea |

| Bloodmoon Dagger | 2 | 8 | Must get wounded for cap |

| Bloodmoon Sickle | 5 | 6 | Take 1 each turn |

And here is the problem: The vast majority of these weapons are under 7 attack in a best case scenario. To win this fight, it’s almost entirely necessary to go over the top. Most of the pool simply cannot do that, starting much, much lower than required.

In short, most of these items are strategic traps.

Roguelites as a genre tend to be about working with you have, trying to make the best decision at any given point in time.

But the end bosses in He Is Coming break that design philosophy. They are so powerful that they close out entire sets of items and strategy designs, as those strategies simply cannot beat them. So instead of making the “best” choice, or trying different builds, I found it necessary to aggressively pre-plan and force a build to defeat them.

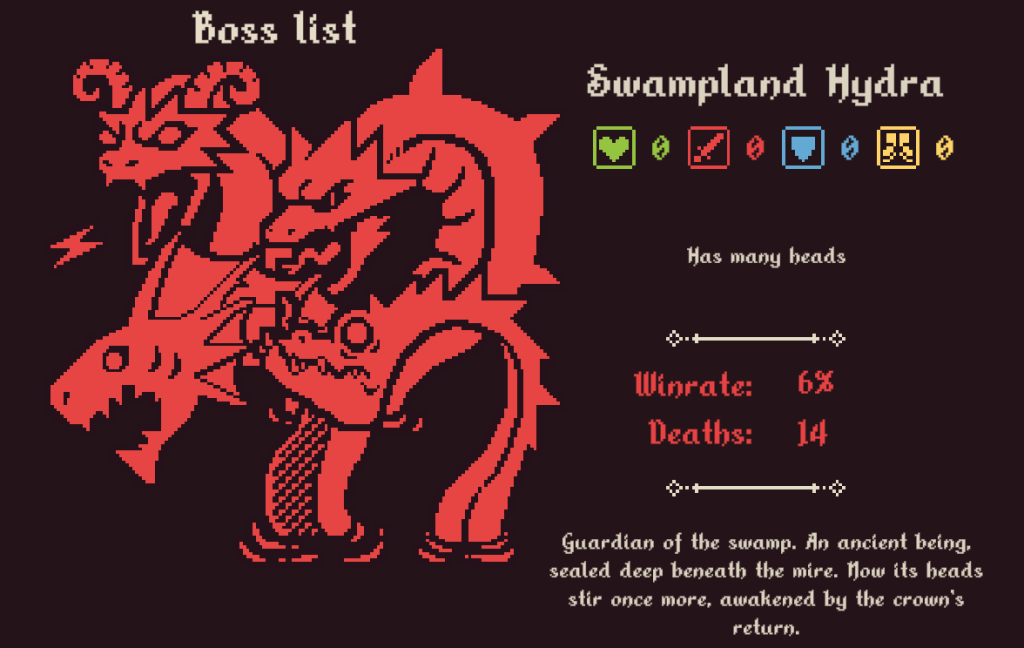

Here’s another example of this: the second zone boss, Swampland Hydra.

This writeup is already pretty long, so I won’t mince words here: I died a lot to the Hydra, before finally discovering a weapon that lets you remove status effects on yourself.

This led me to create a build that uses a status effect called Purity that heals and buffs on removal, and the aforementioned weapon to remove Purity and finally get a kill on this boss. Without using this strategy, the Hydra it builds up too many stacks of different types, and it simply felt impossible to win.

I cannot envision another build to do this. I’m sure it exists. But I’d have to look at every item in the pool, consider how to acquire them, pre-plan the build, and finally execute on it.

I don’t want to do that. I find roguelites fun when I can salvage a run from dumpster, or use knowledge to play around bad luck. But the bosses in He Is Coming just feel over tuned to the point that playing that way can never actually win.

One Other Possibility

I am open to the idea that I am just an idiot. That I have missed a critical portion of this game, or a core mechanic, or something that breaks this whole thing wide open. I know for a fact that I misunderstood how poison worked for almost 5 hours of playtime, leading to an incredibly frustrating loss.

But if I am, I don’t think I’m the only one.

Only about 40% of players have beat the first zone, with 8% beating the second. If I’m just stupid, I’m missing something, so are the vast majority of players.

I made the spreadsheet and those tables and the rest of this garbage because I wanted to see if I was missing something. I wanted to discover if I was misunderstanding a mechanic that would become clear if I just had a slightly bigger brain. A bit more external storage.

I don’t think I am.

Okay, but despite all of this, I actually really like the systems in He Is Coming

So, I’ve spent a lot of time so far discussing how He Is Coming forces a specific style of strategic play in order achieve victory, and how I don’t like that. Which is a bit unfortunate, because it means I’m not talking about the game’s interesting systems, or clever items.

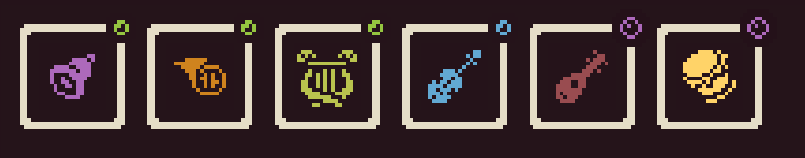

My favorite set of items are probably the instruments, a set of items with the Symphony keyword, meaning that when one of them triggers, all the others trigger as well. It’s a fun idea, making it a bit of shame that they can’t do anything useful.

The backpack is also very neat.

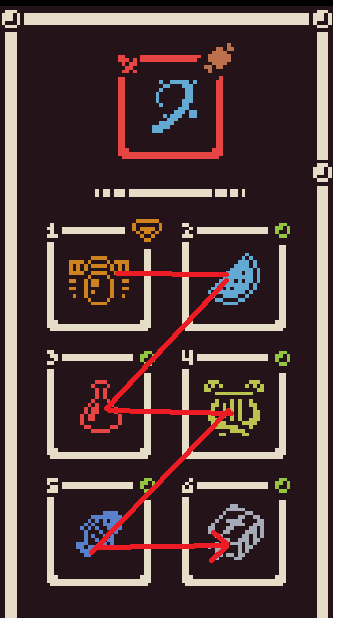

Items trigger from left to right, and top to bottom, meaning it’s possible to set things up to resolve in clever ways. It’s another neat little system, though one I wish was a bit more meaningful to more builds.

Conclusion

I like most of the systems in He Is Coming, but right now I just can’t recommend it because of how it feels to play. It’s in early access, which means things might change, but it also means that they might not.

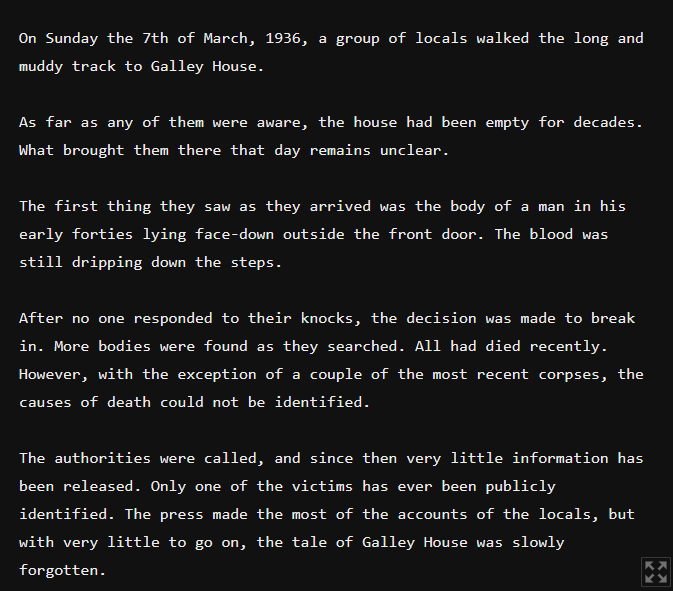

It’s not the worst thing I’ve ever played, but I’m left wishing it was something a bit different. In that sense, it actually reminds of Loop Hero, not just because both have the ye-olde CRT style, but because of the gap between the experience I was hoping for, and the experience I got is wider than I would have liked.

He is Coming is $15 on Steam. If you love the idea of a sort of puzzle roguelite, analyzing builds, and manipulating systems, you might love it. As for me, I’ve had my fill for the moment.