Disclaimer: This post uses real names, and talks about an ongoing conflict. If after reading it, you feel strongly that one side or the other is in the right here, I urge you to channel that feeling into support for that side’s project. Do not harass or make personal attacks against anyone.

Four years ago at PAX East, I played a demo for a game called Sento Fighter. It was a match 3, 1v1 dueling game with a marble selection system, designed by Brother Ming. It was under contract to be published by Penguin & Panda Games. Due to Penguin & Panda’s mismanagement of other projects, it would never go to production.

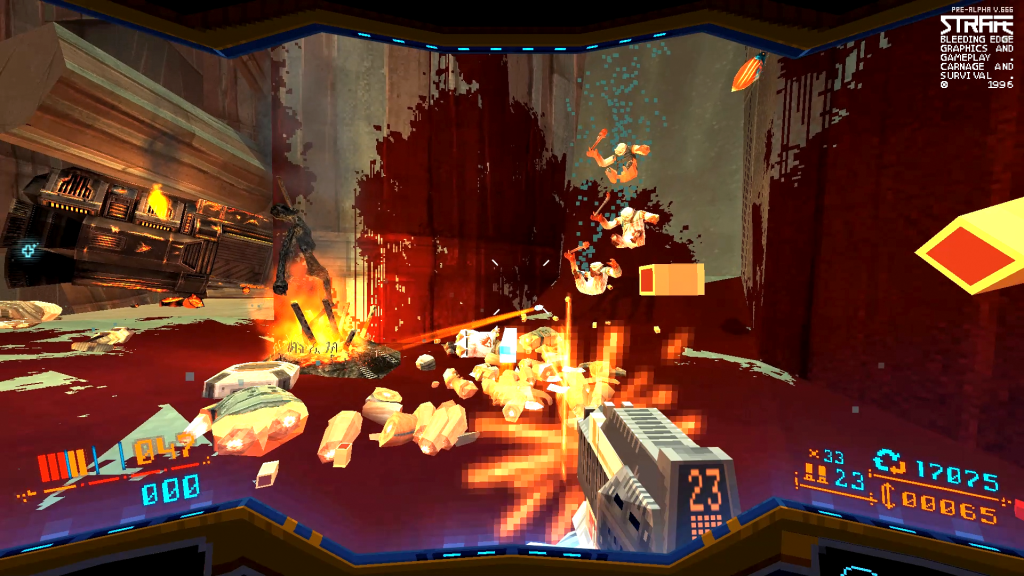

Just under a year ago, at PAX East, I demoed a game called Power Well. It was a match 3, 1v1 dueling with a marble selection system, being developed by Red Planet Games. Red Planet Games was clear with me that it was inspired by Sento Fighter, and initially, right after PAX, Ming was positive about the game.

This past Sunday, the CEO of Red Planet Games, Martin Myles, put up an 8,000 word post accusing Ming of extortion, and calling him a bully. Ming responded by calling Myles a hack who refused to credit him and announcing that he had acquired the rights back to Sento Fighter, and would be publishing it as Re;MATCH. Ming also included a 12-item list of shared mechanics between the games.

So what on Earth happened, and how did we get here?

Table of Contents

Overview

A Timeline of Events

How Law Functionality Works in Board Games

Designers, Developers, and Publishers in Board Games

The Events of July 5th

Welcome to the Court of (my) Public Opinion

Disclosures

Sources

Overview

In the last few days, what began as a private disagreement between Brother Ming (designer of Sento Fighter), and Myles Martin (CEO of Red Plant Games) about whether Brother Ming should be credited as a game designer on Red Planet’s game Power Well, has turned into a full on public feud. This writeup is intended to lay out a timeline for what led to these events, and give some additional context.

Since I don’t want it to get buried, here’s my personal opinion:

1. Brother Ming deserves designer credit for Power Well.

2. Nobody here has publicly broken any laws or committed any crimes. Even if Red Planet Games publishes Power Well and doesn’t credit Brother Ming, they won’t have committed a crime.

3. Taking all participants at their word, I view this mess as more the result of incredibly unfortunate miscommunication and questionable legal ownership of the design than anything else. I’d like to believe no one here set out to rip someone else off without credit, even if this probably paints me as quite foolish.

This is my opinion as of 9/25/24, and it’s quite possible it changes if more information comes out.

Timeline

It’s 2018. Brother Ming begins prototyping a game called Orb Strikers. The rights to Orb Strikers will later be licensed to Jason Moughon for $10,000 and renamed to Sento Fighter.

Jason Moughon is the CEO of publisher Penguin and Panda, and later Big Kid Games. Penguin and Panda successfully funded Kickstarter campaigns for several games, notably Onimaru. Onimaru was expected to deliver in 2019.

P&P failed to fulfill this campaign in a timely manner. There is mixed opinion on Jason Moughan in the board game community. Many backers for projects he ran feel that they have been scammed. They point at his behavior of setting up Big Kid Games after P&P acquired a poor reputation. Other individuals feel that Jason ended up in over his head, and failed to correctly manage the costs of production and delivery, not that he set out to scam people.

But in 2020 Jason still has his reputation intact. Penguin and Panda is demoing Sento Fighter at multiple game conventions, including PAX East and PAX South. Myles plays it, and really enjoys it. He’s excited to see the final product.

Things continue to get worse for Penguin and Panda throughout 2021. They continue to fail to fulfill Onimaru, and some of their distribution partners begin to disavow them, as can be seen here in an archived post from Japanime Games.

As a result, Sento Fighter is never crowdfunded or produced, and exists purely as a Board Game Geek page, a mailing list sign up page, a private Tabletop Simulator Mod, a few photos from conventions, a Penny Arcade post and a single two hour liveplay from collective content group Love Thy Nerd.

Over the next few years, Brother Ming attempts to buy back the rights to Sento Fighter so he can continue development and publish the game, but is rebuffed by Jason.

In 2023, Myles Martin is chatting with his brother, and the two end up discussing Sento Fighter, and wondering what happened to it. After failing to find any info, they decide to attempt to recreate the game. They name their group Red Planet Games.

In January of 2024, the Red Planet Games team feels they have a strong game to demo. They end up getting a booth at PAX East. Brother Ming first learns about Power Well through direct messages from players at PAX East, and is immediately worried that the game is somehow connected to Jason Moughan. This suspicion is largely irrelevant to the rest of the events that follow, except that it does serve to illustrate the miscommunication that will occur between Myles and Ming.

They connect over Discord, and then over the next several months, they will continue to sporadically message, and even get dinner. Unfortunately, while this could have served to defuse the situation, they mostly piss each other off. Below are a few examples.

- Ming comes in initially somewhat suspicious of Jason being involved, as Jason has a history of trying to start new companies to dodge his bad reputation. It’s not helped by the fact that Myles has made really nice prototypes. Miscommunication #1

- Ming tweets about the game to Jerry Holkins, AKA Tycho Brahe, writer for Penny Arcade and founder of PAX. Myles takes this as a sort of attempted flex on him and Red Planet, as opposed to the “Yo, this shit is cool” that it is. Miscommunication #2

- Ming asks Myles to consider hiring the original Sento Fighter artist to do some of the artwork. Myles has a family member doing the art, and so instead takes this request as an insult. Miscommunication #3

- Ming makes suggestions about the ethnicities of the characters. Myles feels that Ming is trying to tell him how to make his game. Ming feels that Myles is taking his own work, and removing his impact on it. There’s a larger discussion here that I’m not qualified to comment on, but I will note that this sort of discussion often comes up between designers and publishers during contract negotiation. Miscommunication #4

- Ming and Myles get dinner to try to sort of calm things down. While there are no “Chat logs” for dinner, Myles comes away from the experience feeling personally attacked. Miscommunication #5!

- Ming notes that Jason might be litigious. Myles decides he needs to make sure his project is above board legally, and will later hire lawyers for advice. This single moment is the match that will ultimately torch any hope of this being resolved amicably.

This all continues to just simmer, right until July 5th where things finally kick off.

But first….

A Brief Note on Legal Matters within the Board Game Industry

I’m not a lawyer. This is not discussing what the law is when it comes to board games, but the current state of how the law seems to actually work here in September of 2024, in the United States. At least in regards to small and medium size board game publishers and designers.

There are a lot of open and expensive questions about the nature of things like copyright, patents, and just the general mess that is intellectual property when it comes to board games. However, unlike the video game industry, nobody in board games has any money. So, nobody sues each other, because they don’t have the money to spend on the lawsuits, and even if they won, it’s unlikely they would recoup their costs.

The end result is that because the industry is so small, everything gets decided in the court of public opinion. If you can convince everyone a game ripped you off, you don’t need to sue anyone. You just convince the public and many people won’t buy the games, because again, this industry is tiny.

Is this good? No. It gives large companies outsized ability to pressure and control terms, while leaving the actual legal questions in limbo because no one can afford to litigate. It allows small scale rip-offs, and copying of games from outside territories. It results in a lot of drama. But it is how things actually currently work.

And now, a second brief bit of context setting.

Designers, Developers, and Publishers in Board Games

The court of public opinion in board game development is a result of norms that exist because of the board game industry’s small size. But it’s not the only weird norm. One easy example to point at is the fact that no one is asked to sign NDA’s at things like Unpub, or for playtests. After all, a legally binding contract doesn’t mean anything if you don’t have the money to enforce it (or if the IP doesn’t legally exist).

Another example is the importance of credit, and properly having credit assigned. Again, this is a small industry. Credit on projects is a resume, and proof of prior work. But different types of credit mean different things. Here’s a very brief overview of some of those types of credit.

Game Designer – This is the person who did the work for most of the game systems, and what is seen as the bulk of the game design work. They made the prototypes, they conceived of the systems.

Publisher – The publisher, on the other hand, often does all of the “not game design” work. This can include, but is not limited to marketing, production, final art, distribution deals. It might also include things like re-theming, or artistic character design. It’s a huge amount of work, which is why game designers often sell their designs to publishers in the first place.

Game Developer – The developer, then, is a sort of intermediary between the two. They often, but not always, work for a publisher. Their job is to take the core elements that a designer has created and bring them to a production-ready state. This can include designing some small mechanical elements of the game, or redesigning systems or themes, or even adding or removing existing mechanics. It’s a complex job and necessary job, but it mostly involves working with a core system they’ve already been given.

The Events of July 5th

Myles’ accusations against Ming stem from this discussion. I’m going to break this down with some images.

This is Ming’s first request.

He asks for 3 things.

1. Credit as a game designer on the Project

2. $1500 to license a character from one of Ming’s other games to the project.

3. A written contract stating they will pay him $3000 if Power Well is successful enough to merit an expansion. There is no guarantee that the game will be.

Myles makes the following counter offer of $4,500, for:

1. A license for a Re:Act Character

2. The ability to provide a non-designer credit for the work Brother Ming did

3. A thank you in the rulebook

4. Brother Ming will stop making any public statements about Power Well in a negative connotation.

Critically, Myles does not want to give Brother Ming a designer credit on Power Well. In his public post, Myles justifies this based on his concern he will open himself up to a lawsuit from Penguin and Panda if he does so.

Brother Ming believes he is entitled to this credit as he designed the core systems that at a bare minimum inspired Power Well.

Ming does not like this offer, primarily because it results in him not being credited as a game designer. He responds with the following counter offer primarily intended to point out how ridiculous it was to not give him designer credit. (Ming has since retrospectively noted that this was “a dumb plan”. )

1. Red Planet Games will pay Ming $11,500 dollars. $10,000 for the design, and $1500 to license a character from Re;Act

2. Red Planet Games will not have to credit Ming as a Designer on the project.

3. All terms from the above discussion.

Myles, after consulting his own industry sources, decides not to respond.

On August 5th, post Gen Con, Ming reaches out to try to explain why the game designer credit is important to him. Unfortunately, while Ming is being sincere, it’s easy to see how someone (Myles) would see this as condescending.

In essence, Ming is trying to get Myles to understand that from his point of view, Red Planet Games has done is mostly development and publishing work, and as such, Ming is owed designer credit.

On August 7th, Myles responds to Ming. He feels attacked by Ming. He does not feel that Ming is a designer on Power Well. He also feels that because Ming sold the game to Jason, Ming isn’t entitled to any more money for the design, and that he has done enough already.

Ming makes one last attempt to convince him. Myles does not respond.

On August 7th, Brother Ming tweets about not receiving credit, and posts a cropped portion of the final message from Myles. This cropped portion does not include the discussion of costs/payment.

Around September 11th, a long term detractor of Brother Ming succeeded in getting one of Ming’s projects DMCA’ed by Nintendo. This individual is not affiliated with Red Planet Games. Ming believes this is the result of the feud with Red Planet Games, though this mostly a matter of personal opinion. While this individual has bragged about this “achievement” on the Red Planet Games Discord, there is absolutely nothing to suggest Red Planet had any involvement in the DMCA request.

In response to Ming’s tweets on August 7th, on September 22nd, Myles posts the document outlining his interactions with Ming.

On September 24th, Ming announces that he has reacquired the rights to Sento Fighter, and plans to relaunch the game as Re;MATCH, and that he will make a public statement in the next few days.

On September 25th, Ming posts his statement. He’s generally in agreement on the timeline, but clarifies several notable points, including his concern around ethnicity of the characters in the game, his actual intentions with the $10,000 offer, and notably lays out a 12 point list of similarities between the two games.

Now that I’ve laid out the publicly provided information of both Myles and Ming, I’m entering the realm of personal opinion.

The Court of (my) Public Opinion

In the time since Myles has posted his statement on the 22nd, I’ve run it past my industry contacts, and some folks in their circles.

Myles chose to put this into the “Court of Public Opinion.” I suspect he’s not going to like the response he gets, especially among designers and small publishers.

Their general take is as follows: While the whole situation is messy, and at some points could have been handled better, Ming is in the right here. Folks have tended to feel that Myles’ statement is not as exonerating as Myles had hoped. To be clear, this was before even seeing Ming’s side of the story.

It’s not a universal opinion. There are people who feel that the distance in time is enough to justify what Red Planet Games have done. But there are even more who feel that it crosses a line to rebuild a game that you already know exists, and try to bring it to market.

While Myles views the work that his team has done as comparable to cloning a video game, that’s not how the board game industry is likely to see it. Instead, it appears to them that Myles is attempting to rip off someone else’s design, refusing to pay or give them credit, and then rush it to market as a product, not for the love of making games.

Like I said earlier, I’d like to think no one set out to be an asshole here. I’d prefer to believe that Myles’ lack of familiarity with the industry has led him to cross a lot of lines he may not have been familiar with. Frankly, that probably will do nothing but make me look like a naive idiot to both sides. So be it.

That said, while I’m going to try to keep my distance here, I’m going to make one big suggestion to Red Planet Games: Ban the person who has been attempting to harass Ming and DMCA Ming’s projects from your Discord server. You’re doing yourself absolutely no favors by even passively giving the appearance of endorsing the actions of someone who uses anonymous harassment and legal threats as a cudgel against others.

What Red Planet Games has done is generally against industry norms, but they have every legal right to produce and sell Power Well, and never mention Ming again. I don’t think they should.

Why I’m Writing This

I’ve been following both of these projects for quite some time, and I was initially enthusiastic about both. My (frankly terrible) writeup on Sento Fighter is one of the earliest posts on this blog. I was really looking forward to Power Well.

I feel strongly that Brother Ming deserves credit on Power Well for his work that the game very clearly, at a minimum, cribs from. Initially, this didn’t seem like it would be an issue, as Myles and others told me at PAX East that they would doing so.

When things turned sour, I wrote, but chose not to post a write-up detailing why I thought Ming deserved credit. At the time I would just have been starting drama, and I figured that I might not have the full picture. I suspected that there might be info related to Penguin and Panda that might make Myles feel he could not credit Ming in a fair manner without opening himself up to a lawsuit, something I was dead on the money about.

However, as Myles and Ming have now both made their sides of the story clear, and for public viewing, I no longer feel that I’m either out of the loop, or misinformed as to the thoughts and feelings of the primary actors here. While some of the information presented has caused me to carefully reconsider my own thoughts and run them past those more familiar with the industry, I’m ultimately still convinced that Ming deserves Game Designer credit on Power Well.

Disclosures

My name is John Wallace, and I often go by Fritz. I’m the primary writer/owner of Gametrodon. I don’t work in the game industry on any level, but I do have a few contacts and connections with those who do.

The extent of my connections with the two primary folks involved here, Brother Ming and Myles Martin are as follows:

1. I’ve interviewed Brother Ming previously about the nature of fan projects, mostly in regards to Mihoyo and their policies. I also reached out to him for some clarification on statements made prior to posting this writeup, and prior to the release of his public response.

2. I chatted briefly with Myles Martin at PAX East this year about Power Well, and played a demo. I was planning to reach out to get his point of view right before he put up a 8000 word public statement on Sunday.

Sources

Myles Martin’s Initial Statement

Ed Note: When Myles refers to J in his censored documents, he’s talking about Jason Moughan of Penguin and Panda, and Big Kid Games.

Brother Ming’s Response

Neither Myles nor Ming have debated the authenticity of the messages posted.

However, for pretty obvious reasons, they have fairly different takes and feelings about the nature of the interactions, and characterize them quite differently.

I’ve taken backups of these statements, but linked to the source. Should that source go down, I will be hosting the statements myself. This article was written with the content as it was on 9/22/2024 for Myles Statement, and 9/25/2024 for Brother Ming’s statement.

Updates/Revisions:

Any changes/updates to this post made after it has gone live will be noted here.

5/15/2025 Update: Both of these games were at PAX East 2025, and are gearing up to move into launching Kickstarters possibly in the next year, so I’ll be quietly observing. In the event that the original source of the statements are removed/changed, I’ll be putting up my backups, but that doesn’t seem to be an issue yet.