The presents have been opened. The award lists that people actually read have been posted. The games industry itself has been gutted like a fish, along with the rest of the technical sector.

Ah, 2023.

It’s surprising to me that the first year that truly felt “post” COVID was still such an incredibly shitty year in so many ways on a global level. Usually I wrap up the year with a list of dead games. But that sort of thing feels less important than, say, the thousands and thousands of layoffs.

Instead, it’s time for the return of the Gametrodon Placeholders.

As always, the criteria are simple: winners must be something I played this year and wrote about on Gametrodon. And unfortunately, that means that I can’t just give all the awards to Baldur’s Gate 3 and call it a day, because I haven’t finished it, nor have I done a writeup on it.

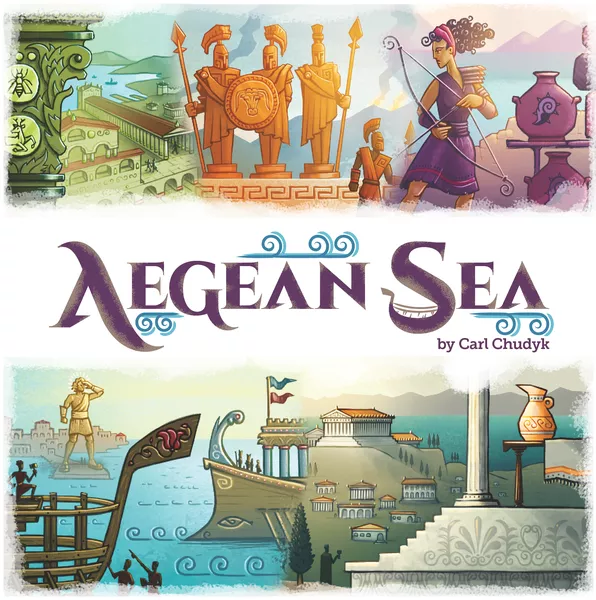

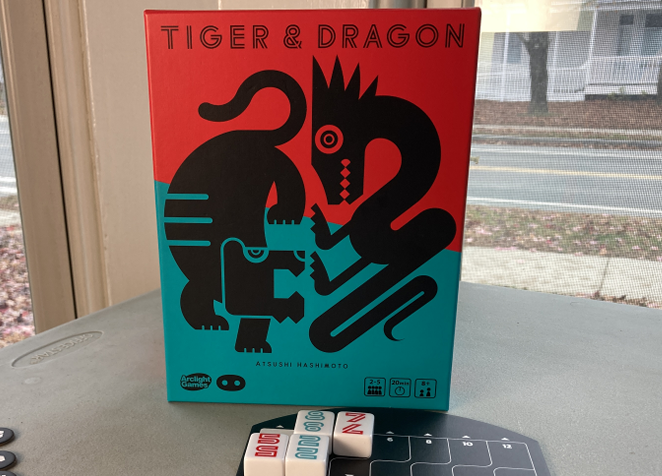

Best Board Game

I played a lot more board games this year than I did last year, in a lot more genres than usual. That said, there was only a single game that I played over a dozen times, at multiple different events, with different people, and even sat down and randomly taught to strangers.

A game so generally agreed to be “pretty good” that everyone in the group I played with went and bought their own copy of the game. As such, it’s the obvious winner.

It’s Tiger and Dragon.

It’s not the most complex, or thematically rich, but it very quickly became the go-to game of the group I play with. It’s the game everyone wants to play, and is simple enough to teach quickly to boot. In short, it’s the best because it got the most play with the most people, and the least friction.

Honorable Mentions: Clank Legacy, Quickity Pickity

Best Soundtrack

The criteria to even be in the running for Best Soundtrack is pretty simple: was it good enough to add to my running playlist? Even though currently that playlist is mostly just my “Waiting for my feet to heal” playlist, one game easily beat out the competition.

It’s Pizza Tower.

There’s not too much more to say on this. The music is just too damn good. Pizza Tower is an equally fantastic game that I didn’t feel too equipped to evaluate. But if nothing else, it’s the only music this year that really made me want to start swinging at folks.

Honorable Mention: Baldur’s Gate for that one bit, and maybe Herald of Darkness from Alan Wake 2. But I didn’t play that game, I just love the song.

Best Multiplayer Shooter

I’m going to be honest. This one is mostly a tie between this game, and the game in the runner up slot. But the game in the runner up slot has about a billion more sales than the winner, and I’d rather bring more attention to the smaller one.

The best multiplayer shooter of the year is Deceive Inc.

I don’t love everything about the game, but I’d much rather have more interesting and weird multiplayer shooters with multiple paths to victory, and unusual mechanics.

The runner up is, of course, BattleBit, which I think everyone has played at this point, but still deserves it. And as I’ve already observed, this was effectively a tie. But if I’m giving an award, I’d rather it be to something like Deceive Inc that not everyone has heard about.

Game Of The Year

Remember that inclusion criteria I mentioned up above?

I lied.

The game of the year is Baldur’s Gate 3.

Have I done a writeup on this game? No. Hell, at 65 hours, I haven’t even finished a single full playthrough.

It’s some of the most fun I’ve ever had, and is ridiculously flexible as a game. It’s also far from technically perfect. I spent at least 6 of those 65 hours trying to fix bugs or errors, and having to reload save files. That said, it’s probably the pinnacle of PC games at the moment: incredibly well designed maps, the greatest voice acting ever, fairly interesting combat, and just generally an excellent game.

:strip_icc()/pic7034945.jpg)