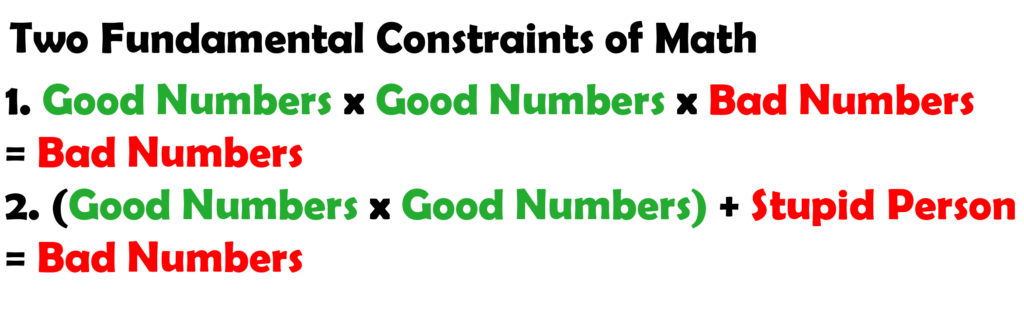

Hi. I’m the stupid person who gives review scores! You might know me from the byline of a million terrible reviews on Kotaku, GameInformer, or other gaming media sites swallowed up into useless reviews, copy pasted guides, and SEO milking trash. I might also not be real, and be a product of Chat GPT, but it’s not like you would know.

Of course, when I say that I give review scores, that isn’t entirely true. See, I can’t actually give a super low score, because that would make us look bad to the companies that purchase a majority of our advertising. And I can’t give too high a score either. So really, the editor gets to give out the score. And edit my review to make it work.

Here’s my job: I play a copy of Starfield, or Armored Core, or what have you two weeks before release for 10 hours, and then I have to write 50 pieces of junk about it for the next three months. I bet you think you’d like that wouldn’t you? Well, I’ve spent the last eight hours writing about how Elden Ring could be in the Armored Core universe. It isn’t, but rent is due, and I need those clicks.

Sure, I do have to give out that 8/10, but it’s not like I have any real choice in the matter. And yeah, my actual job is churn out garbage at a rate high enough that the internet will be flooded with white noise, in an attempt to boost our pages over a fandom wiki.

You know, at one point in time I really liked games.

I miss that time.

But hey, it’s fine. It’s good that we gave it an 8. After all, it’s not like art is subjective, and review scores are an ultimately pointless attempt to access a complex series of functions, and provide little to no value. I can’t really even blame consumers for this one. It’s not like you woke up and hounded us to assign arbitrary numbers to every piece of entertainment media over the last thirty years.

Frankly, it’s probably pretty good that I can just act like it’s your fault for being upset. It was kind of awkward when everyone started asking questions about nepotism, and how industry connections worked, and who actually assigned review scores.

Bit of a lucky break for us that “Ethics in game journalism” turned out to be a dog-whistle for neo-nazi misogynists. If they’d been reasonable instead of being jackbooted fascists for even 30 seconds, maybe people would have listened to what they were saying. And maybe even asked some questions!

Questions like, “Wait, is all your advertising coming from the product you’re reviewing?” and, “Is all gaming news just an incestuous cycle of freebooting and regurgitating press releases?” Something, something, even a racist and women-hating clock can be right about journalism twice a day and all that.

But that didn’t happen, and now we can continue to blame you, the consumer, for being angry and stupid, while we do our best to turn your search results into the world’s least helpful internet thread when you try to look up where to find an item.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to put up 800 words on how Animal Crossing is coming to Pokémon Go, or my car gets repossessed. And if you could follow my twitter real quick, that would be great, since that’s where I put all of my real opinions about this hobby I used to love.