I got back late last night from another Winter Weirdness, one of the events hosted by Green Mountain Gamers, a group that organizes game days in the Vermont/New Hampshire area. I quite like these events.

It’s a very lightly structured event. Folks bring their personal games to the event to lend to other people for the event, and then just spread out to play games.

As always, I’ll be talking about what I played, what I liked, and anything else about the event that strikes my fancy.

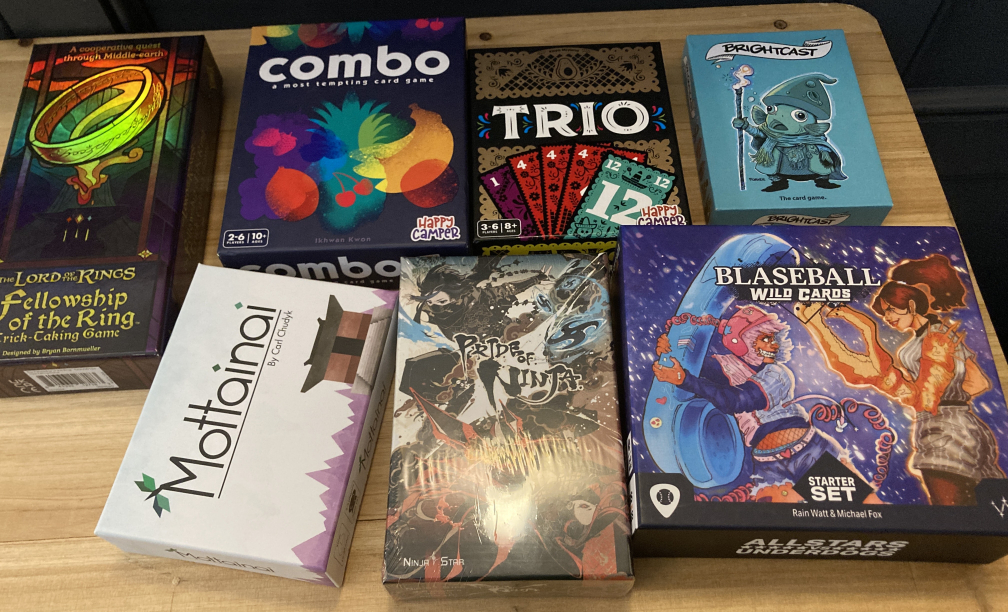

The games I brought

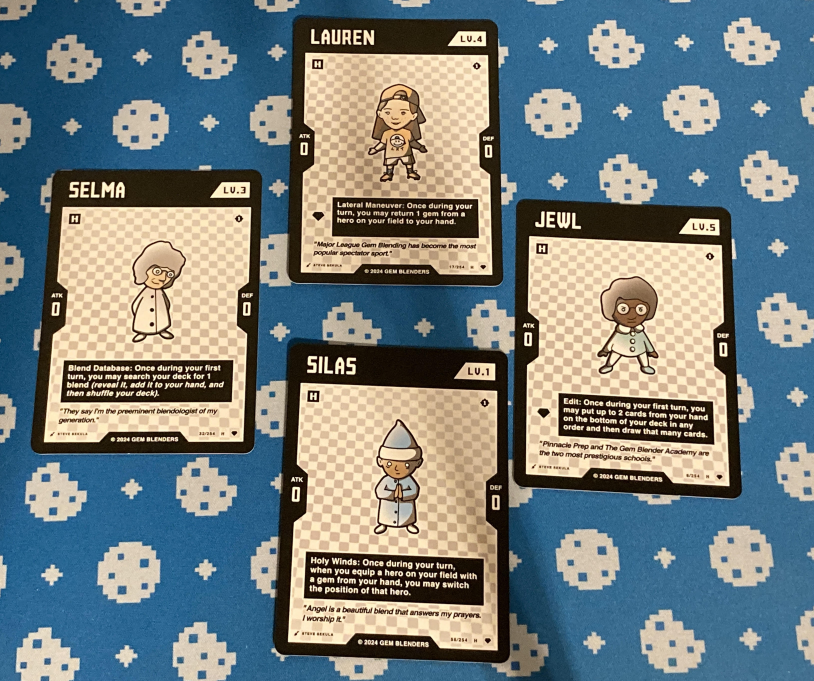

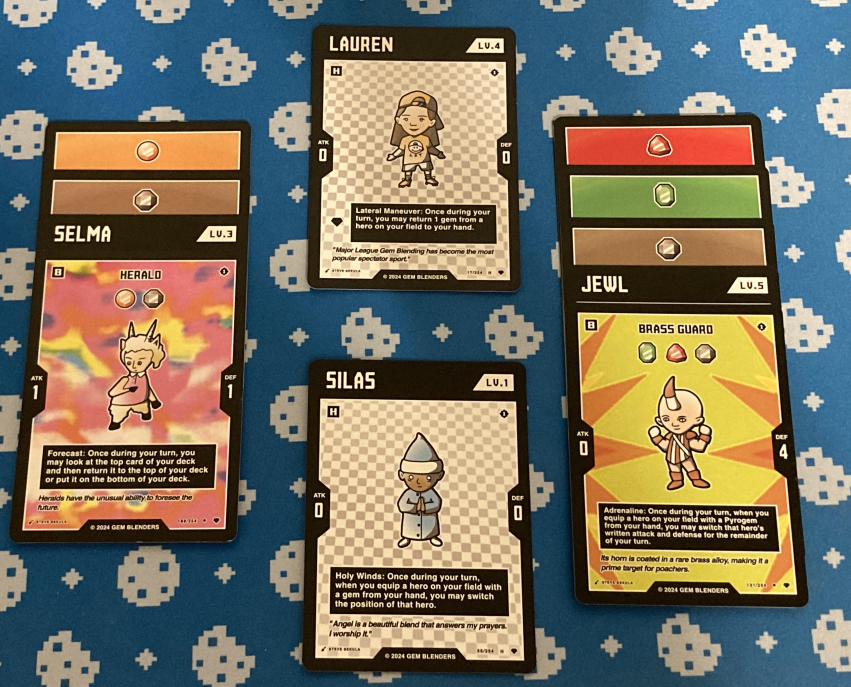

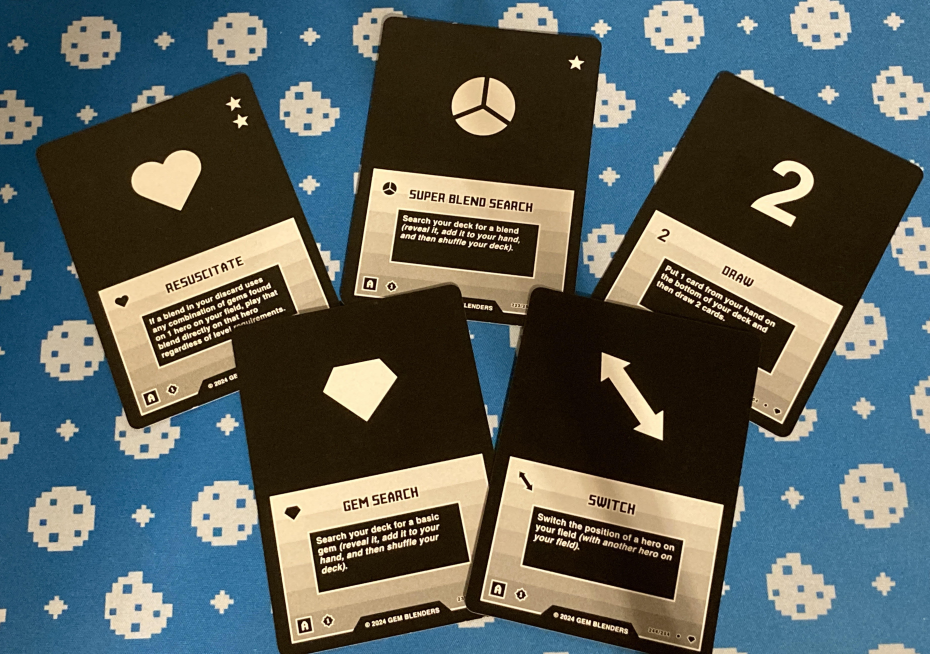

I brought a smattering of stuff, including Mottainai, Combo, Trio, Pride of Ninja, Brightcast, Blaseball Wild Cards, and the first LoTR trick taking game. These were all small, and I was able to to stuff them into a bag. I’ve linked the ones I’ve done reviews for up the blog, but I enjoy all of these, and someday I really need to give Trio it’s own write-up.

Game time

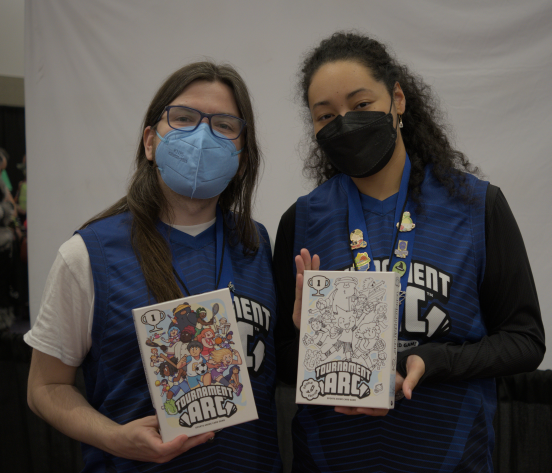

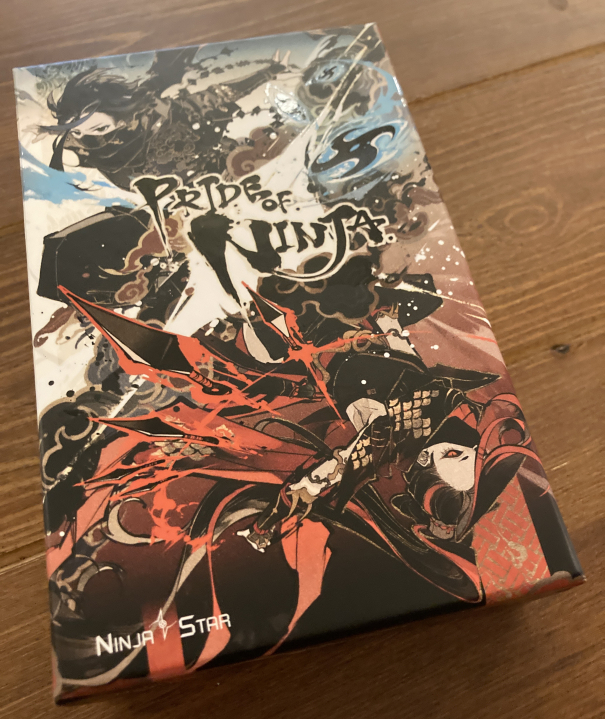

First thing I did once I got there was crack open my copy of Pride of Ninja, and recruit a few people to play with me. I’ve been interested in Pride of Ninja ever since I first saw it two years ago at PAX Unplugged, and having actually managed to buy a copy this year, I finally got a chance to sit down and try a full game.

I really like it! It’s a pick and pass drafting game with what I’d consider to be two small twists: First, after everyone takes a card, players either reveal that card, and place it in a front row slot, or keep it hidden and place it into a backrow slot. This means that as the draft goes on, you get some information about what your opponents are doing, but it’s still possible to hide key pieces.

Secondly, many of the cards work in such a way that you need to care more about what your opponents are doing, and a few can be effective tools for either punishing them, or drafting off their success. What I really liked about these cards though is that it never really felt particularly painful to be on the receiving end of these plays.

Pride of Ninja is great.

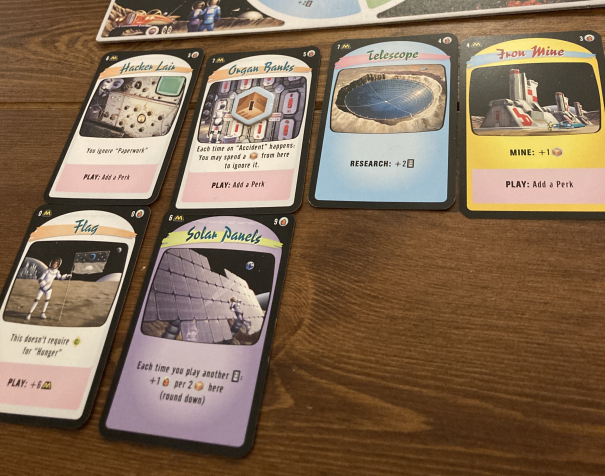

Next up was Moon Colony Bloodbath. This was a weird one.

Moon Colony Bloodbath is a tableau builder where you build up, and then lose your tableau. Well, you do if you’re me. If you’re winning, less of said tableau ends up blown away by accidents, infighting, and malfunctioning robots. The player power graph goes up, and then it goes way, way down.

My feelings on Moon Colony Bloodbath is a decided sense of “Hmm”. I don’t know if I disliked playing it because it’s a bit undercooked, or because I just lost every game horribly. During the back half of the game, once my starting supply of colonists had been whittled to nothing, and I was forced to liquidate buildings, there was a sort of dull sense of a boredom instead of a comedy of overconfident self-destruction.

It felt like the final turns of a game of Terraforming Mars, where instead of doing anything interesting, you just min-max for victory points, as there isn’t enough time for any grand scheme to actually come to completion.

I also have a really weird complaint about the games art and theming. The game feels like it wants to be doing a sort of 1950’s-60’s pop-sci/science fiction cover thing. I think this is a really good theme, and standing alone the art is fine if not great, but in conjunction with the rest of the games mechanics, it feels like the artist was never in on the joke. Every location is played fairly straight, every robot just looks like a generic robot. It feels like no one told Franz Vohwinkel that each of these colonists was going to meet a horribly grisly death.

Anyway, with those two finished, I switched over to a few quicker games. This included a few rounds of Tiger and Dragon, a quick playthrough of the first level of the Lord of the Rings Trick Taking Game, and a short game of Combo. No notes here except maybe a reminder to myself that I should actually do a writeup on Combo one of these days.

After all of that, I played Panda Royale. I don’t like Panda Royale. This might be a bad game between the fairly aggravating draft order system, the dull dice types, the pointless and tedious arithmetic, and also the fact that the theme has absolutely zero connection to the mechanics of this sloggy roll and write.

This was followed up by doing a 4 person draft of Edge of Eternities to round out the day. Unlike the other several times I’ve drafted this set, I actually did quite well this time, and manged to win almost all of the games I played.

And then it was time to leave.

Oh…

The Barre Social Club

This event was held in Barre Social Club, and I just want to note that it might be the single most beautiful space I’ve ever been in.

There’s all this great old furniture, and the walls are covered in old maps, magazines, playbills, and other fun bits of old paperwork.

Like, just look at it.

Oh, and this bookcase?

It’s a secret door!

Okay, not that secret, it leads to a kitchen space, but like… still! Isn’t that cool?

It’s a coworking space, so if you’re in Barre, might be worth checking out. Anyway, that’s all for me right now, I’m gonna see if I can write something to put up for today about a specific game. Talk more later.